Crypto-Keynesian Lunacy

My article on smart contracts has had quite a reaction, much like the blockchain article before it. I’ve had a lot of praise and criticism on the article, much coming from the Ethereum/altcoin crowd which didn’t like what I said.

Chief among the critics vying for my attention is one Kyle Samani, who more or less threw the kitchen sink at my arguments in the form of a 19 message-long tweet storm about my article. I don’t follow him on Twitter and wouldn’t have noticed, were it not for him specifically pinging me on telegram to take a look.

Now, I don’t normally spend my time arguing with people that are seeking to waste my time, but in this case, I’m going to make an exception because he so clearly embodies what I call Crypto-Keynesian lunacy. In this article, I’m going to make the case that the economic world view of people like Kyle are fundamentally what drives his criticism and not the technical or social reality.

Crypto-Keynesian Fallacy #1: Aggregate Numbers Tell an Accurate Story

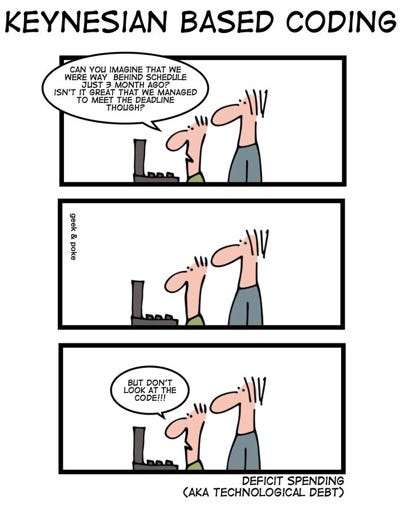

The first argument for smart contracts is that there’s a lot more “developer activity” on Ethereum’s Turing-complete Solidity. This argument is about as useful as focusing on aggregate demand and aggregate supply that Keynesians love so much. Economic activity by itself doesn’t tell you anything. People could be trading the same egg back and forth for a dollar a billion times and that would count in the economic activity statistics as a billion dollars of activity. The aggregate numbers simply don’t mean very much because they have at best a very weak correlation with the actual value added.

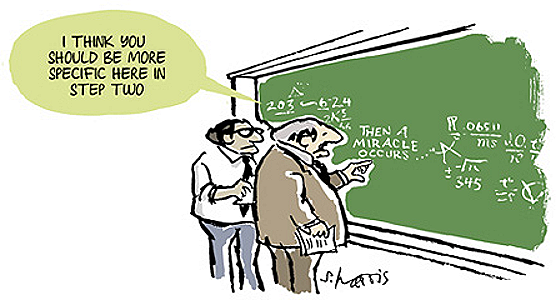

Belief that developer activity actually means a lot is mistaking action for value. It’s true that creating value requires activity, but not all activity adds value. In fact, a lot of activity reduces value. Actually figuring out which activity is valuable and which add nothing or even have a negative effect is not easy and requires a lot of research and technical due diligence. This is why Keynesians focus on easily measured numbers, not on actual reality. Looking at easily measured numbers is much easier than doing the hard work of actually evaluating complicated situations. Crypto-Keynesians do the same thing.

If you look at protocol development Bitcoin has many more devs. Most of the “developer activity” on Ethereum is in ICO development and not protocol development. ICOs have been a cash cow for ICO issuers for over a year now. But raising money does not mean you’re adding value any more than digging and filling a ditch adds value. Most of these projects have zero users or even a product. Many haven’t released anything for years, nor do they need to since they have no obligations to the token holders.

In other words, developer activity is a really poor proxy for usefulness or value-add and ultimately, activity does not mean success. Google Glass, for example had a lot of developer activity, but that didn’t mean it was actually useful, viable or successful.

Crypto-Keynesian Fallacy #2: Centrally Designed Systems Work Better than Organic Bottom-Up Reality-Tested Systems

Keynesians are famous for their faith in central planning, especially as a way to increase demand. Entire industries like health care, education and housing have felt the heavy hand of government intervention and desire to do “what’s best for us” despite our protests. Crypto-Keynesians are the same way. Their faith in centrally planning products perfectly from the outset is astonishing and largely driven by hopium.

What’s more, a lot of these centrally designed systems are much less efficient and require a lot more overhead. Provably fair gambling can be done without the large overhead of an expensive blockchain. You can prove something existed at a certain point in time without the cost of millions of transactions that get replicated thousands of times. The hubris of central planning is that they not only think everything will work, but that it’s the best solution from the outset.

But that’s assuming something works. Most of the projects in the crypto space have added zero value. In fact, many have swindled, scammed and stolen as to subtract value. The fact that so many projects have failed to deliver value should be humbling. Instead, for a Crypto-Keynesian, this is only evidence that the big use-case are just around the corner and that new and interesting breakthroughs are only a few months away. They believe that raising money/hiring people is evidence that actual value is about to be delivered soonish™.

The bottom-up reality is that most people simply don’t care to use these systems unless heavily incentivized to do so. Usually, that means that the users are actually investors, which is a nice way of saying that the users are really in a Multi-Level Marketing scheme searching for new investors that will use the systems in the same way.

Systems are really, really hard to design and are very rarely right the first time. As any startup veteran will tell you, it’s really hard to find a product-market fit and many not only try different models, but often pivot to entire different industries for that reason. Successful startups try lots of things to see which things work and iterate. The best startups find solutions to existing problems. By contrast, most of these crypto startups are trying to find problems for the crap that they want to build.

What’s really scary about blockchain systems is that you really can’t iterate or change things very much without throwing out all pretense of decentralization. Thus, Crypto-Keynesians have to believe any investments they make will be correct and successful on the first try. This is simply not the reality of complex systems or markets. At best, the iterations in these projects are very slow, enormously expensive and really hard to change.

Crypto-Keynesian Fallacy #3: Everyone Will Do Things Exactly As Expected

The most hilarious part of Kyle’s tweet storm was saying how the NBA.com server would be the source of truth and therefore, Oracles could be trusted and smart contracts can be useful for non-digital stuff.

Remember, the Oracle is the last word on the smart contract. There is no further adjudication in a decentralized setting. You can’t appeal to another judge should something go wrong. You simply have to accept whatever the Oracle says.

Apparently, this enormous attack surface an Oracle adds is not really even considered. Who controls the data feed from nba.com? Can that get hacked? Would anyone in a gambling situation be incentivized to affect this feed? Say you got 100–1 odds on the Cavaliers when they were down 3–0 to the Warriors and bet $1M on the Cavs. Would you have incentive to hack the servers so you could be paid out in a bearer instrument? Would you be incentivized to bribe the nba.com IT guy? Would you kidnap the person’s family? After all, you would only need to change the Oracle’s vote. Given that the ambitions of these projects are to take over the entire sports betting market ($3B/yr), this is not just theoretical.

An adversarial network requires a lot of thought about the actual incentives. In addition, the more complicated the system is, the more you have to test out what holes in the incentive structure there might be. Most of these projects are ridiculously complicated. Bitcoin, by comparison, is orders of magnitude simpler and less vulnerable in terms of incentive structure. To think that you’ve designed an incentive structure that’s correct on the first try is absolute lunacy and reflects a lack of real world experience.

The usual response by a Crypto-Keynesian when faced with such questions is to refer you to some added incentives in the system like additional Oracles, bonded Oracles, or some such. It’s usually a half-baked idea that anyone can figure out holes to in 5 minutes, but that’s the normal response. There’s probably a solution to every possible attack vector, but most of the time, each “solution” creates an even bigger attack surface. Eventually the solutions get so complicated and so hard to analyze that the flaws can only be revealed by the cold, hard slap of reality.

Conclusion

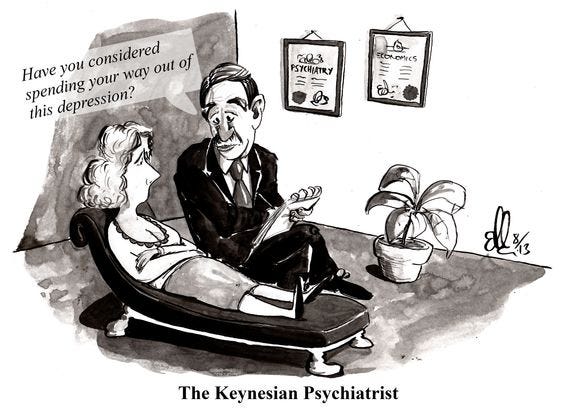

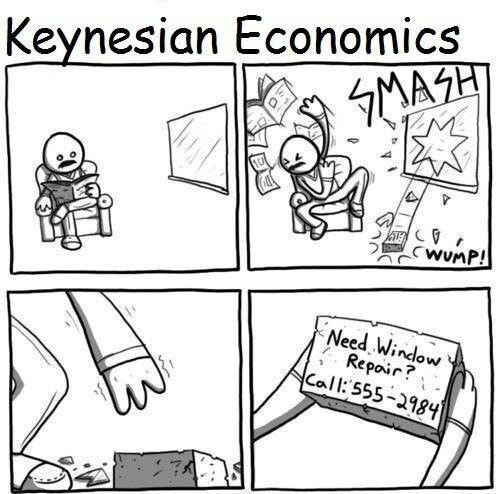

The real weakness of Keynesianism is the belief you can get something for nothing. It’s the broken window fallacy in a macro form.

Crypto-Keynesianism makes essentially the same error. Developer activity by itself means very little. Centralized systems generally don’t work very well on the ground. Incentives are really hard to get right. This is why we have so many ICOs. They are “doing something”, but not adding value. You may be raising money, you may be hiring people, you may be donating to some causes but you’re not adding value until the market buys your product or service. And no, you don’t get to brag about how “successful” you are until you’ve actually added value and not anytime before then.

The real innovation was and always has been Bitcoin. Bitcoin is sound money and sound money is what allows you to preserve value over the long term. That, in turn allows people to save for large capital projects which, in turn, build up civilization. Crypto-Austrians believe this is the basis for building in the future, not in these pie-in-the-sky projects that don’t deliver value.

Crypto-Keynesians believe success is simply having money. They are two separate things. You can make money by adding to civilization or you can make money by rent-seeking. The former should be applauded. The latter should be despised.

The ICO boom makes clear that Crypto-Keynesians can’t tell the difference. This leads to the building products that add “activity” but fail in delivering any sort of value, in effect digging and filling ditches and pretending that means something. This is Crypto-Keynesian lunacy.

Comments are closed