The Truth about Smart Contracts

Much like the words “blockchain”, “AI” and “cloud”, “smart contract” is one of those phrases that get a lot of hype.

After all, what can be better than being able to trust what will happen instead of using the judicial system? The promises of smart contracts include:

- Enforcing contracts automatically, trustlessly and impartially

- Taking out the middle men in contract construction, contract execution and contract enforcement

- (By implication) Removing lawyers

I sympathize with the hype. After all, how much more efficient could things be if we could just remove the need for trusting the other party to execute?

What the heck is a smart contract, anyway? And isn’t that the domain of Ethereum? Isn’t this the way of the future? Why would you stand in the way of progress?

In this article, I’m going to examine what smart contracts are and the engineering reality that goes with it (spoiler: it’s not so simple and very hard to secure).

What is a Smart Contract?

A normal contract is an agreement between two or more parties that binds them to something in the future. Alice may pay Bob some money in return for use of Bob’s house (aka rent). Charlie may agree to repair any damage to Denise’s car in the future in return for a monthly payment (aka car insurance).

What’s different about a “smart” contract is that the conditions are both evaluated and executed by computer code making it trustless. So if Alice agrees to pay Bob $500 for a couch for delivery 3 months from now (aka couch future), some code can determine whether the conditions are true (has Alice paid Bob? has it been 3 months yet?) and do the execution (deliver the couch from escrow) without giving either party the ability to back out.

The key feature of a smart contract is that it has trustless execution. That is, you don’t need to rely on a third party to execute various conditions. Instead of relying on the other party to make good on their word or even worse, relying on lawyers and the legal system to remedy things should something go wrong, a smart contract executes what’s supposed to happen timely and objectively.

Smart Contracts are Pretty Dumb

The use of the word “smart” implies that these contracts have some innate intelligence. They don’t. The smart part of the contract is in not needing the other party’s cooperation to execute the agreement. Instead of having to kick out the renters that aren’t paying, a “smart” contract would lock the non-paying renters out of their apartment. The execution of the agreed-to consequences are what make smart contracts powerful, not in the contracts innate intelligence.

A truly intelligent contract would take into account all the extenuating circumstances, look at the spirit of the contract and make rulings that are fair even in the most murky of circumstances. In other words, a truly smart contract would act like a really good judge. Instead, a “smart contract” in this context is not intelligent at all. It’s actually very rules based and follows the rules down to a T and can’t take any secondary considerations or the “spirit” of the law into account.

In other words, making a contract trustless means that we really can’t have any room for ambiguity, which brings up the next problem.

Smart Contracts are Really Hard

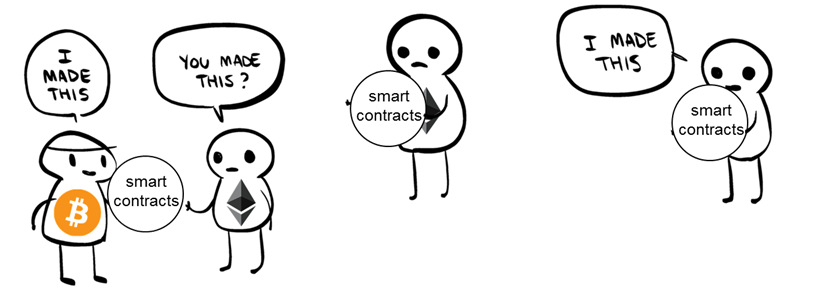

Because of a lot of centralized marketing from Ethereum, there’s a mistaken belief that Smart Contracts only exist in Ethereum. This is not true. Bitcoin has had, from the very beginning in 2009, a pretty extensive smart contract language called Script. In fact, smart contracts existed before Bitcoin as far back as 1995. The difference between Bitcoin’s smart contract language and Ethereum’s is that Ethereum’s is Turing-complete. That is, Solidity (ETH’s smart contract language) allows for more complicated contracts at the expense of making them more difficult to analyze.

There are some significant consequences of complexity. While complex contracts can allow for more complicated situations, a complex contract is also very difficult to secure. Even in normal contracts, the more complicated the contract it is, the harder it gets to enforce as complications add more uncertainty and room for interpretation. With smart contracts, security means handling every possible way in which a contract could get executed and making sure that the contract does what the authors intend.

Execution in a Turing-complete context is extremely tricky and hard to analyze. Securing a Turing-complete smart contract becomes the equivalent of proving that a computer program does not have bugs. We know this is very difficult, as nearly every computer program in existence has bugs.

Consider that writing normal contracts takes years of study and a very hard bar exam to be able to write competently. Smart contracts require at least that level of competence and yet currently, many are written by newbies that don’t understand how secure it needs to be. This is very clear from the various contracts that have been shown to be flawed.

Bitcoin’s solution to this problem is to simply not have Turing-completeness. This makes the contracts easier to analyze as the possible states of the program are easier to enumerate and examine.

Ethereum’s solution is to place the burden on the smart-contract writers. It is up to the contract writers to make sure that the contract does what they intend.

Smart Contracts Aren’t Really Contracts (at least on ETH)

While leaving the responsibility of securing contracts to the writers sounds good in theory, in practice, this has had some serious centralizing consequences.

Ethereum launched with the idea that “code is law”. That is, a contract on Ethereum is the ultimate authority and nobody could overrule the contract. The idea was to make clear to smart contract developers that they’re on their own. If you screwed up in making your own smart contract, then in a sense, you deserve it. This came to a crashing halt when the DAO event happened.

DAO stands for “Decentralized Autonomous Organization” and a fund was created in Ethereum as a way to show what the platform could do. Users could deposit money to the DAO and get returns based on the investments that the DAO made. The decisions themselves would be crowd-sourced and decentralized. The DAO raised $150M in ETH when ETH was trading at around $20. This all sounded good in theory, but there was a problem. The code wasn’t secured very well and resulted in someone figuring out a way to drain the DAO out of money.

Many called the person draining the DAO of money a “hacker”. In the sense that the “hacker” found a way to take money from the contract in a way not intended by the creators, this is true. But in a broader sense, this was not a hacker at all, just someone that was taking advantage of the quirks in the smart contract to their advantage. This isn’t very different than a creative CPA figuring out a tax loophole to save their clients money.

What happened next is that Ethereum decided that code no longer is law and reverted all the money that went into the DAO. In other words, the contract writers and investors did something stupid and the Ethereum developers decided to bail them out.

The fallout of this incident is well documented. Ethereum Classic was born, preserving the DAO as written and conserving the “code is law” principle. In addition, developers began shying away from using the Turing-completeness property of Ethereum as it’s proven to be hard to secure. ERC20 and ERC721 standards are the most frequently used smart contract templates in Ethereum and it’s important to point out that both types of contracts can be written without any Turing-completeness.

Smart Contracts Only Work with Digital Bearer Instruments

Even without Turing-completeness, smart contracts sound really good. After all, who likes having to go to court to get something that rightfully belongs to them trustlessly? Isn’t using a smart contract much easier than normal contracts?

For example, wouldn’t real estate benefit from smart contracts? Alice can prove she owns the house. Bob can send money for the house and get the house in exchange. No questions of ownership, trustless, fast execution by machine, no need for judges, bureaucrats or title insurance. Sounds amazing, right?

There are two problems here. The first is that smart contract execution by a centralized party is not really trustless. You still have to trust the centralized party to execute. Trustlessness is the key feature, so centralized execution doesn’t really make sense. To make smart contracts really trustless, you need a platform that’s actually decentralized.

That leads us to the second problem. In a decentralized context, smart contracts only work if there’s some definitive link between the digital version and the physical version. That is, whenever the digital version of the house changes ownership the physical version has to also change ownership. There’s a need for the digital world to “know” about the physical world. This is known as the “Oracle problem”.

When Alice transfers the house to Bob, the smart contract needs to know that she actually transferred the house to Bob. There are several ways of doing this but they all have the same essential problem. There has to be some trust in some third party to verify the events in the physical world.

For example, the house could be represented as a non-fungible token on Ethereum. Alice could transfer the house to Bob in an atomic swap for some amount of ETH. Here’s the problem. Bob needs to trust that the token actually represents the house. There has to be some Oracle that ensures the transfer of the house token to him actually means that the house is his legally.

Furthermore, even if a government authority says that the token actually represents the house, what then happens if the token is stolen? Does the house now belong to the thief? What if the token is lost? Is the house not available to be sold anymore? Can the house token be re-issued? If so, by whom?

There is an intractable problem in linking a digital to a physical asset whether it be fruit, cars or houses at least in a decentralized context. Physical assets are regulated by the jurisdiction you happen to be in and this means they are in a sense trusting something in addition to the smart contract you’ve created. This means that possession in a smart contract doesn’t necessarily mean possession in the real world and suffers from the same trust problem as normal contracts. A smart contract that trusts a third party removes the killer feature of trustlessness.

Even digital assets like ebooks, health records or movies suffer from the same problem. The “rights” to these these digital assets are ultimately decided by some other authority and an Oracle needs to be trusted.

And in this light, Oracles are just dumbed down versions of judges. Instead of getting machine-only execution and simplified enforcement, what you actually get is the complexity of having to encode all possible outcomes with the subjectivity and risk of human judgment. In other words, by making a contract “smart”, you’ve drastically made it more complex to write while still having to trust someone.

The only things that can work without an Oracle are digital bearer instruments. Essentially, both sides of the trade need to not just be digital, but be bearer instruments. That is, ownership of the token cannot have dependencies outside of the smart contracting platform. Only when a smart contract has digital bearer instruments can a smart contract really be trustless.

Conclusion

I wish smart contracts could be more useful than they actually are. Unfortunately, much of what we humans think of as contracts bring in a whole bunch of assumptions and established case law that don’t need to be explicitly stated.

Furthermore, it turns out utilizing Turing completeness is an easy way to screw up and cause all sorts of unintended behavior. We should be labeling smart contract platforms Turing-vulnerable, not Turing-complete. The DAO incident also proved that there’s a “spirit” of the contract which is implicitly trusted and helps resolve disputes more so than we realize.

Smart contracts are simply too easy to screw up, too difficult to secure, too hard to make trustless and have too many external dependencies to work for most things. The only real place where smart contracts actually add trustlessness is with digital bearer instruments on decentralized platforms like Bitcoin.

Comments are closed